Motivation is one of those things that we all seek, but can struggle to find. For leaders (parents, teachers, school leaders, coaches, CEOs), the ‘Holy Grail’ is to have motivated people with the passion to drive their own success. We want people who are focused on getting better, with the aim of being the best version of themselves. Yet half the time we’re left questioning ourselves, “Why don’t they just do it?”

Why do we need to know about motivation?

One of the biggest difficulties leaders have when working with novices is disengagement and more often than not it can be put down to a lack of motivation. This can come out as negative behaviour because they are trying to avoid the activity. As I talk about later, motivation is domain-specific and not linked to the person, so we actually have the ability to influence how novices approach tasks by setting it up in the right environment. Also, “learners’ intrinsic motivation dramatically deteriorates with increasing age, and during the teenage years many learners have lost interest in and excitement for school (Ryan & Deci 2020).

In education, I see unlocking motivation as one of the keys to locking out negative behaviour and then being able to enter the curriculum through positive learning behaviour.

Leaders need to create the environment that allows this sort of person to develop. This can be particularly difficult when dealing with external pressures or tasks that we must do without being given choice (high-stakes testing, funding that is based on data, time constraints). I’ve come up with this ABCD(E) of Motivation model as a way of explaining what the research says about motivation and how we can deal with the external pressures.

If you are motivated, you learn better and remember more of what you learned.

Kou Murayama, associate professor at the University of Reading

Self-Determination Theory

As I have learnt more about Self-Determination Theory, I have found that it has reinforced a lot of my personal thoughts on motivation. In this article, I’ve given a brief overview and refer to certain aspects throughout, but I encourage you to check out their website (selfdeterminationtheory.org) for more info.

Self-Determination Theory: Deci and Ryan say that Self-Determination Theory “represents a broad framework for the study of human motivation and personality.” They speak about three basic psychological needs:

- Autonomy: a sense of initiative and ownership in one’s actions. Having choice and being able to do things willingly.

- Competency: the feeling of mastery

- Relatedness: sense of belonging and connection

The Continuum

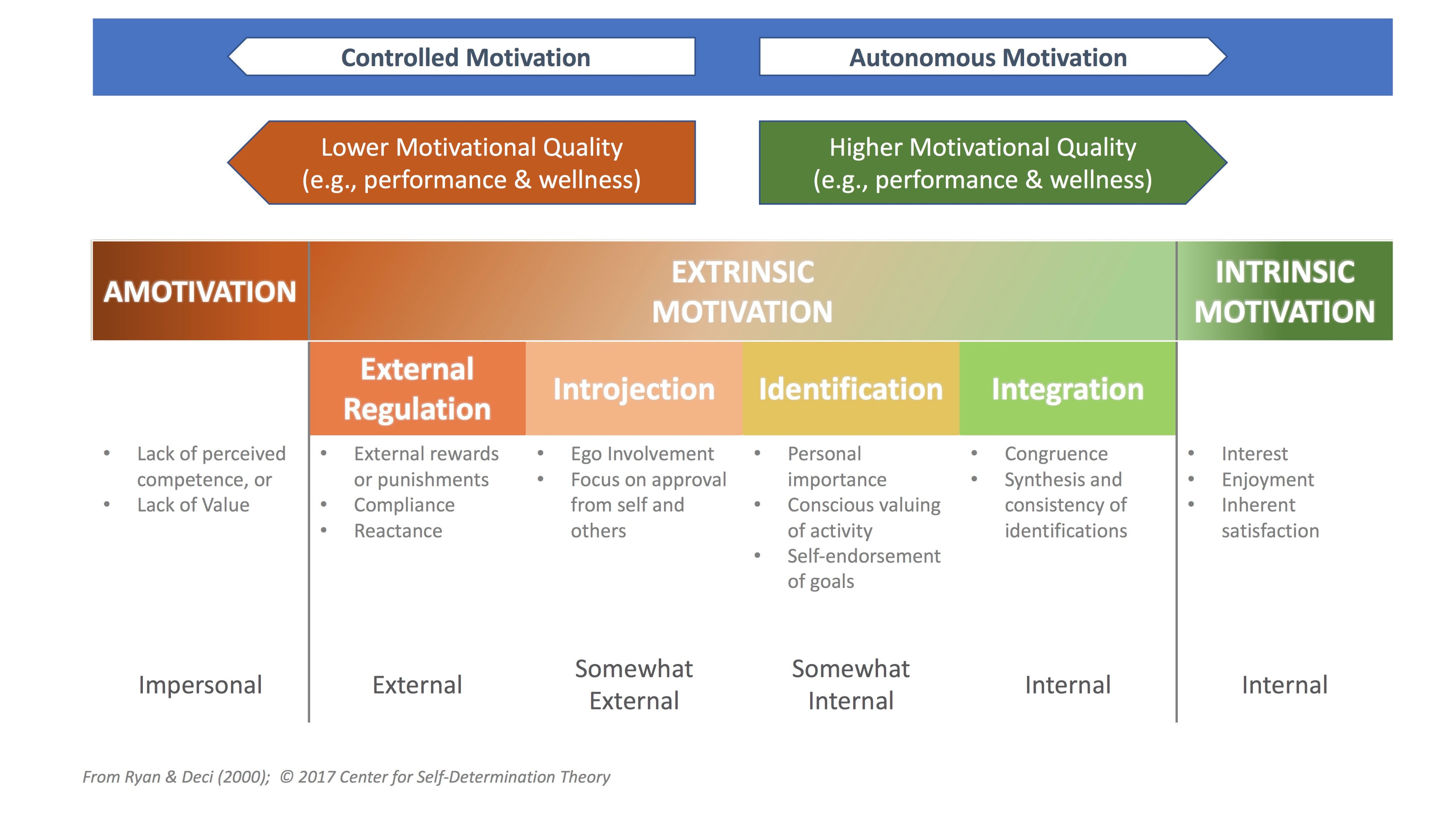

When looking at motivation, we usually talk about extrinsic versus intrinsic, but Self-Determination Theory looks more at controlled or autonomous motivation. Controlled is when we might coerce them to do something by offering a reward or threatening punishment. While autonomous is where we do things willingly through choice.

There are internal extrinsic motivators such as identified and integrated regulation where we do activities not because we necessarily enjoy them, but because they link to our goals, values and interests. It might be something like deliberate practice where we work on our times tables or practice passing a ball because we know it will help us get better.

Scenario

In education, we often punish students who are actually just lacking in autonomous motivation. For example, you are starting a new lesson and straight away a student begins exhibiting disruptive behaviours (calling out, making jokes, talking to others). We may choose to remove this student, who then misses out on further instruction time.

Upon returning, they get extremely frustrated at not being able to complete the task. They look around them and see that everyone else is able to show their understanding. This negative comparative judgement and lack of competence leads to further task-avoidance behaviour which is probably even more attention-seeking. Once again, the student will probably be isolated. However, they are probably content with this because then they don’t have to do the learning (which is hard).

To move away from this sort of scenario, the ABCD(E) Model looks at moving people towards autonomous motivation which in turn will lead to an increase in school achievement, performance, self-esteem and overall well-being (Ryan and Deci 2020).

What is the ABCD(E) of Motivation?

Coming from a sporting background and then moving into teaching, I have always been intrigued with motivation. Many classes have left me wondering why some students have this drive to do their best, while others will do their best to avoid doing their best! I have come up with this model on motivation as a way of trying to simplify the knowledge I have gained from learning about psychology and cognitive science.

The way that I have approached this model is as a series of options that we can take as leaders when working with a new group or starting a new unit or work. I feel knowing these five principles are vital for understanding why people do what they do.

Achievement

ACHIEVEMENT: If we experience achievement or pleasure early, we are more likely to pay attention in the future (Shimamura, 2018)

“Attention is the currency of the classroom”

Peps Mccrea, Motivated Teaching

Experiencing early success is vital for building intrinsic motivation. As Peps Mccrea puts it, we are more likely to pay attention if we believe it is a wise investment to do so. If we can link current scenarios with previous positive experiences, we can remember how good it felt and will therefore apply ourselves towards it.

Shimamura, 2018 tells us that pleasurable experiences stimulate the release of dopamine. The same neurochemical that is activated by cocaine, nicotine, eating chocolate, looking at attractive faces and listening to music. From birth, we start to connect this positive feeling with success e.g. the way our first steps are celebrated.

Our learners need to know what success is. They need to know:

- Where are they going?

- What does it look like?

- How can they get there?

- How are they going?

Achievement leads to attention

Think about times when you or your kids have played a new game and failed. What was the attitude towards future participation like? As experts, we need to set them up for success by starting them off at an accessible level to ensure the goal is achievable. We know that they’re going to need hard work in order to improve, but that doesn’t sound like much fun, does it?

The novice needs to be given the right level of support through things like scaffolding, modelling and worked examples so that they can get that release of dopamine by experiencing success. When developing lessons we need to think about how it will be perceived by our students.

After the initial success or pleasurable experience, then we can start to create the challenge. Mccrea calls this ‘precise pitching‘, which means that we should provide learning experiences that are challenging, yet achievable for as many pupils as possible. This is supported by Bjork & Bjork, 2011, who have labeled it ‘desirable difficulties‘ to enhance learning through things like spacing, interleaving and elaboration. Meaning we want to create challenges that aren’t too easy or too hard.

Think about how video games are developed. They have different difficulty levels (easy, medium, hard) and set it up so that the player progresses through the game with each stage gradually getting harder. Gamers get ‘hooked’ from the start because they know what the goal is, they experience success and ‘desirable difficulties’. I have written an article for ACHPER NSW about Gamification in PE.

Better

BETTER: Focus on getting better, not being the best (Kirschner and Hendrick, 2020)

It is natural to be driven by performance. We are surrounded by people who are classified as the best – sport stars, social media influencers and celebrities. Yet, we only see the destination point of these people and not necessarily the hard work that went into getting them there (I’m sure it’s hard being a social media influencer!).

Achievement Goal Theory says that Mastery Goals put the “focus on learning and mastery of the content or task (Kirschner and Hendrick, 2020).” It takes the focus off comparing their performance to others and avoids looking at how they have been judged. Getting better is continuous. while being the best has an end point.

If we focus on being the best (performance-approach goal), our thoughts on success will always be influenced by others and the final result will be out of our control. The last goal orientation approach is called Performance-Avoidance Goal – where people don’t want to lose or fail. This can be the worst kind of goal because it can lead to people not even participating, just so that they avoid failing.

People who apply the mastery approach are also more likely to seek feedback. Which in turn will lead to further success (if the right type of feedback is given, see below).

How to create a culture focused on improvement

We need to change our language so that it is focused on the process, rather than the end result (see how NRL player, Nathan Cleary demonstrates this here). However, what makes this difficult is that we are surrounded by moments where society celebrates performance outcomes. It’s all about who won, not how did you play. Cleary speaks about the process so often because his whole organisation is behind this mindset shift. Moving away from thinking about winning, to thinking about how they need to perform.

Part of the reason why sporting teams find it so difficult to win back-to-back premierships is because they can lack the intrinsic motivation to push as hard as they did the previous season because they have already achieved their goals. If we shift our focus towards improvement and getting better, our athletes understand that they are on a continual pursuit of excellence.

After an exam, rather than asking, “What did you get?” you could ask, “How did you find it?” or “What did you do well?” Now, we certainly still need to celebrate success, but that success doesn’t have to just be results orientated. It could be celebrating when someone persists with a task despite getting it wrong initially. Highlighting the behaviour that we want to see in the future.

Teaching our learners to focus on the things they can control ensures that they can attribute success to what they have done and can link their success to effort. As teachers, this is where Dylan Wiliam’s work on formative assessment and feedback is so important. It focuses our feedback on giving the learner information on what to do next. Prioritising this feedback loop tells the learner that it’s not just about getting the right answer, but understanding and improving. This can be achieved through things like:

- handing back gradeless work with comments only

- giving students mixed sets of feedback and work. Then the students have to try to match up the feedback with the work

- get students to use a rubric, success criteria and exemplar to self and peer-assess

Promoting learning as a journey, not a destination

In education, we need to promote learning as a journey, not a destination. To really allow this approach to work, changing community attitudes is needed to move away from just focusing on winning. A culture needs to be created where people feel psychologically safe to fail and be vulnerable.

Once again, this culture can only be created by promoting the behaviours that we want to see. Doug Lemov in Teach Like a Champion, talks about ‘positive framing‘, where we look to guide our students to act the way that we know they can, through correcting and encouraging their behaviour. It’s also about leading by example and sharing your true self, which I talk about later in Connection.

“What Chinese parents understand is that nothing is fun until you’re good at it.”

Amy Chua, author of The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother

In order to sustain motivation, we need to feel like we are good at it. Not many people will say that they are having fun if they are continually bad at something. So, leaders need to ensure that they help shape the way learners perceive success. This is achieved through explicitly communicating to learners what the checkpoints of success are and specifically what they need to do to get there. It doesn’t have to be boring and repetitive, but to truly get good at something it will take practice.

Connected

CONNECTED: When we feel connected (to the person and/or people, the concept and/or the activity), we are more likely to be motivated to invest our attention (Geary, 2008; Willingham, 2021)

Connection is the power source of motivation

There are a number of ways that connection can build motivation. Feeling connected to the:

- person leading (e.g. teacher/coach/CEO)

- people involved with the task (e.g. team/group)

- the subject/concept/theme e.g. Mathematics, JFK Assassination, Living things

- the actual activity or question itself

Arthur Shimamura talks about building curiosity through asking interesting questions, exploring new environments, asking “aesthetics” questions (How they feel about things) and through storytelling. Sparking curiosity is all about getting them to want to know more. The aesthetic questions engage the emotional brain circuits and force us to organise our own thoughts.

This is also supported by Daniel Willingham, 2021 who writes about how the comedian, den mother, storyteller and showman were classified by students as being effective teachers because of their ability to make boring material interesting! He also wrote about why storytelling is so effective because of the 4 C’s of a good story:

- Causality

- Conflict

- Complications

- Character

Telling stories builds both curiosity and connection for the learner. This is because it grabs their attention and then keeps it because they are easy to comprehend, the learner has to continually think about the links (which are supported by the causal structure of a story) and then make inferences of the meaning.

Word of caution

“I am sure that got her students’ attention. I am also sure it continued to get their attention – that is, to distract them – once the teacher was ready for them to think about something else.”

Daniel Willingham, Why don’t students like school?

As teachers, we naturally try to develop activities that we hope will be engaging for our students. Where we can go wrong is if our ‘hook’ or ‘attention grabber’ ends up being too good and we can’t get our students to re-focus on the actual learning part. We still need to ensure the main thing, is the main thing!

How can we increase connection?

One of the reasons why novices can struggle to connect with new concepts and ideas is because the expert suffers from the curse of knowledge and doesn’t pitch at the right level. This means that the new idea is too abstract for the learner. Thought needs to be put into the right starting point so that we can engage the learners straight away. We need to ask ourselves what are the prerequisites for connecting with this concept? What vocabulary will they need? Would they have experienced something similar?

Elaboration Theory (which I’ve previously written about here) addresses turning abstract ideas into more concrete ones through what Charles Reigeluth calls Epitomes. This can be achieved by:

- using actual manipulatives in mathematics

- playing a modified version of a game in PE

- going on an excursion to a place or at least watching a video about the place

- telling a story or using analogies that students can understand

Be vulnerable

Trying something new means that we need to be vulnerable to failure. How can we expect the people we lead to put themselves in these positions if we don’t model it to them ourselves? Vulnerability also gives novices an opportunity to connect to your story and see how you navigated your way past mistakes. It could also be admitting when you’ve made mistakes in the classroom or modelling how you’re learning something new.

Do they feel connected?

I’ve previously written about How to create a positive classroom culture and a lot of it links up to ensuring students feel connected to their teacher and as a group.

Mccrea says we need to make “the process of learning easy, whilst keeping the content of learning challenging.” He also emphasises the importance of ‘nudging norms‘ and ‘breeding belonging‘. I don’t think I would have to highlight to any leader how important building relationships is, but what actually has more influence are the group norms and whether they feel part of that group.

Think about when you walk into a classroom and the energy of the room causes you to immediately feel tense and heightened. It could be noisy, lots of movement or even deathly silent. This phenomenon is called emotional contagion where we begin to mirror the emotional feelings of others around us. As leaders, we want to nudge this in a positive direction to create a supportive environment.

An example of a whole school approach that demonstrates a focus on building these connections comes from Parkville College. In partnership with Department of Education and Training, Victoria they put together the High Impact Engagement Strategies document with the aim, “To make the school fit the student, rather than the student fit the school.” It includes three stages of engagement:

- Building trust: Empathy, Unconditional Positive Regard, Relationship Building

- Co-creating the climate: Pragmatics, Predictability, Explicit Behavioural Expectations

- Engaging authentically: Motivating towards Change, Dancing with Discord, Self-Regulation→Co-Regulation

Domain-specific

DOMAIN-SPECIFIC: Motivation is domain specific, meaning we are motivated by particular things, we are not necessarily motivated people (Hendrick and Macpherson, 2017)

There are no motivated people, just people who are motivated

Why is it that it seems like your student can’t sit still for two minutes in the classroom, but will sit fixated on the screen playing Mindcraft for hours!? It’s because they have experienced things that have previously been mentioned such as success and connection. This has built up their capacity to want to get better. Combine this with the storylines, attention-grabbing graphics and community and you have a recipe for a motivating activity!

For each new lesson/theme/concept that we introduce, we need to think about what our students prior-knowledge and experience will be. If we fail to help our novices make the connection in their new domain, they will disengage with their learning.

Things like self-efficacy and having a growth-mindset (where you believe that you can achieve) won’t necessarily make us successful, but it can contribute to keeping us motivated to keep persisting (Kirschner & Hendrick, 2020). However, it still changes depending on the setting.

People who come across as driven, are likely to have developed an understanding of the importance of finding purpose and connections with what they do and also developed the mindset of getting better, not being the best.

Extrinsic motivators

EXTRINSIC MOTIVATORS: Only use if intrinsic motivation is lacking. It may provide a boost to motivation, but often fails to last long term or provide meaningfulness (Weinstein et al 2019)

Rewards don’t bring success

As you’re probably starting to work out, there is no clear-cut way to motivate people. “Dangling a carrot” might work for one person, but could then do the complete opposite for someone else. What makes it even trickier is that it might even work one day, but then have no-effect the next!

I put the E in brackets for the ABCD(E) Motivation Model, because we only want to use external motivators as a boost. They may help bring success, but if we become reliant on them, the “well will eventually run dry.”

When do educators negatively influence motivation?

- monopolising learning materials

- telling students answers

- issuing directives

- using controlling words such as “should” and “have to”

- Giving grades! They’re often experienced as controlling

- Performance goals: where we focus on students outperforming others

- High-stakes tests

What can educators do to move towards autonomous motivation?

- Offer meaningful choice: leads to increase in ownership

- Take student interest into account when designing lessons/tasks

- Give students opportunities to speak and listen to them

- Acknowledge improvement and mastery

- Make time for independent work

- Offer structure with clear goals, expectations and rules

- Appropriate level of scaffolding

External motivators can be like chocolate

Some people love chocolate, while others hate it. Some people will do anything for it, yet others only want it sometimes. The same applies for rewards. Whether it’s being used to recognise an accomplishment, to motivate a change in behaviour or to emphasise a teaching strategy, it will never work all the time for everybody.

In Running the Room, Tom Bennett talks about the problems of rewards being:

- We condition children to expect a reward for doing what should be normal

- Some children are disproportionately rewarded

- Reward value is contextual

External extrinsic motivators might seem like a nice thought or gesture, but it can quickly turn pear-shaped! For example, we might give our children a special present for coming first in something at school. This then tells them that winning is important and secondly that they can expect a present every time they win something! What happens if the next time, you don’t give them the present?

Even when we say things like, “I’m doing it for my kids!” or “Dad would be proud!” These are examples of introjection external motivators and they can help push us to success however, it won’t provide us with the higher-motivational qualities of increased wellness and satisfaction. They can also lower self-determination for people who already have autonomy and are intrinsically motivated.

Motivated to avoid punishment

Similar to being driven by the thoughts of other people or rewards, trying to avoid punishment can motivate people to act a certain way, but it’s not going to cause long-lasting changes. Getting unmotivated people doing things that they don’t see the relevance of will only lead to further disconnection to the person dishing out the punishment or the task they are being forced to do.

Final words on motivation

When leading unmotivated people, we want to try to start off by helping them connect with the teacher/leader, group/team, subject/theme or activity/lesson. We then want them to experience achievement or pleasure in what they are doing. This will hopefully help the person to move further along the self-determination continuum towards feeling more autonomous in what they are doing.

Unfortunately, there is no one way that will work for everyone all the time. Each individual and scenario will present their own challenges. However, having an understanding of what can increase motivation can hopefully help you create the right environment for those that you lead.

Overview

ACHIEVEMENT: If we experience achievement or pleasure early, we are more likely to pay attention in the future (Shimamura, 2018)

BETTER: Focus on getting better, not being the best (Kirschner and Hendrick, 2020)

CONNECTED: When we feel connected (to the person/people, the concept/subject and/or the activity), we are more likely to be motivated to invest our attention (Geary, 2008; Willingham, 2021)

DOMAIN-SPECIFIC: Motivation is domain specific, meaning we are motivated by particular things, we are not necessarily motivated people (Hendrick and Macpherson, 2017)

EXTERNAL MOTIVATORS: Only use if intrinsic motivation is lacking. It may provide a boost to motivation, but often fails to last long term or provide meaningfulness (Weinstein et al 2019)

References

Bennett, T. 2020. “Running the room: The teacher’s guide to behaviour.” John Catt Educational Ltd

Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. 2011.” Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning“. In M. A. Gernsbacher, R. W. Pew, L. M. Hough, J. R. Pomerantz (Eds.) & FABBS Foundation, Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (pp. 56–64). Worth Publishers.

Geary, D.C. 2008, “An evolutionarily informed education science“. Educational Psychologist, 43 (4), 179-195

Hendrick, C. and Macpherson, R. 2017, “What does this look like in the classroom? Bridging the gap between research and practice” John Catt Educational Ltd

Kirschner, P.A., & Hendrick, C. 2020, ‘How Learning Happens: Seminal Works in Educational Psychology and What They Mean in Practice.’ David Fulton Inc

Lemov, D. 2020, “The Coach’s guide to teaching.” John Catt Educational Ltd

Lemov, D. 2021, “Teach like a champion 3.0: 63 Techniques that Put Students on the Path to College.” John Wiley & Sons Inc

Mccrea, P. 2020, “Motivated Teaching: Harnessing the science of motivation to boost attention and effort in the classroom” CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

Poed, S., Cowan, I., Swain, N. 2020. “The High Impact Engagement Strategies (HIES).” Parkville College,

Department of Education and Training, Victoria.

Reigeluth, Charles. 1979, “In search of a better way to organize instruction: The elaboration theory (05). Journal of Instructional Development. 2. 8-15. 10.1007/BF02984374.

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L. 2020, “Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions,” Contemporary Educational Psychology, Vol 6

Shimamura, A. 2018, “A Whole-Brain Learning Approach for Students and Teachers.”

Weinstein, Y., Sumeracki, M. and Caviglioli, O. “Understanding how we learn: A visual guide.” Routledge

Willingham, D.T. 2021. “Why Don’t Students Like School? A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom. Second Edition.” John Wiley & Sons Inc